The world is a complex system, and our usual way of thinking is making it more so.

Today’s organization is influenced by a complex array of stakeholders: customers and customer advocates, industry and associations, competitors, media, management, union and employees, SIGS, financial institutions, environmentalists, and suppliers, as well as government and society.

To further divide this already complex system seems ludicrous, yet that is what many organizations do every day by employing analytic thinking.

Dividing problems into smaller parts is not the solution, as Peter M. Senge writes in The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization: “Dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants. Systems are alive and their character depends on the whole. To understand difficult managerial problems or plot strategy, you’ll have to see the whole system [and its environment] that generates the issues.”

SYSTEMS VS. MACHINE-AGE THINKING

In The Fifth Discipline, Senge succinctly captures the situation with which we’re faced: “From an early age, we’re taught to break apart problems in order to make complex tasks and subjects easier to deal with. But this creates a bigger problem... we lose the ability to see the consequences of our actions, and we lose a sense of connection to a larger whole.”

This “lesson” probably took hold of our society during the Agricultural Age. Many social theorists believe that today’s problems stem from that age, when we found ways to dominate nature and make it subservient to our immediate needs.

The Industrial Revolution — or Machine Age — furthered that dominating mode through its mechanistic revolution, fueled by the intent to conquer Mother Nature. And it worked—or so we thought.

The mechanistic approach to effecting change is no longer viable. As Russell Ackoff reminds us, “We are attempting to deal with problems generated by a new age with techniques and tools that we have inherited from an old one.”

In Ackoff’s view, the Machine Age spawned three fundamental concepts — reductionism, analysis and mechanization — that must change in our Systems Age.

The Fundamental Concepts of the Machine Age

Reductionism: The premise is that if you take something apart or reduce it to its lowest common denominator, you will ultimately reach indivisible elements. For instance, in reductionism, the parts of the cell are the ultimate components of life.

Analysis: A powerful mode of thinking, analysis takes a problem apart, breaking it into its components. At that point, you solve the problem, then aggregate the solutions into an explanation for the whole. Therefore, analysis tends to explain things by the behavior of their parts rather than the whole! Even today, analysis is probably the most common technique used in corporations. Managers “cut their problems down to size,” reducing them to a set of solvable components and then assembling them into the solution as a whole. Analytic thinking is still so much our norm that many people continue to see analyzing as synonymous with thinking. Instead, synthesis or holistic Systems Thinking is what’s required.

Mechanization: This seeks to explain virtually every phenomenon by resorting to a single relationship: cause and effect. However, mechanization has a major consequence; once we find the cause, we believe we don’t need anything else, so the environment becomes irrelevant. Indeed, the whole effort of scientific study is about relationships studied in isolation and in laboratories—a closed-systems view of the world. Mechanization colored how we looked at the world as a whole. It brought us assembly lines, mass production and countless machines, as well as the idea that we live in a mechanistic world instead of an organic, human one. We have gone from thinking of machines as a means of mass production to thinking of the world as a machine—not as Mother Nature with a will and a mind of its own.

Appearance and Reality

While the reductionist, analytic and mechanistic approaches may appear to resolve ongoing problems, they actually fail to provide long-term, permanent solutions.

Analytic thinking is perhaps the biggest culprit among them, because it is such a common way of thinking that we’re hardly aware of it. Because its central, linear approach is to problem-solve only one issue at a time, other issues must wait their turn. This is the inherent deficiency of this thinking mode, and this alone can cause problems.

Simple analytic thinking focuses on cause-and-effect: one cause for every one effect. It asks the all too common either/or question.

Its weakest link—and the reason it’s not working today—is that it doesn’t take into consideration the environment, other systems and the multiple or delayed causality that surrounds each cause and effect. Nor does it consider a part’s interrelationships and interdependencies with other parts.

Seeing the Whole System

At first glance, Systems Thinking may appear more complex and multilevel than analytic or reductionist thinking. But familiarity with its central concepts helps simplify and detect order in complexity, and it accommodates our understanding of reality in a more fundamental way.

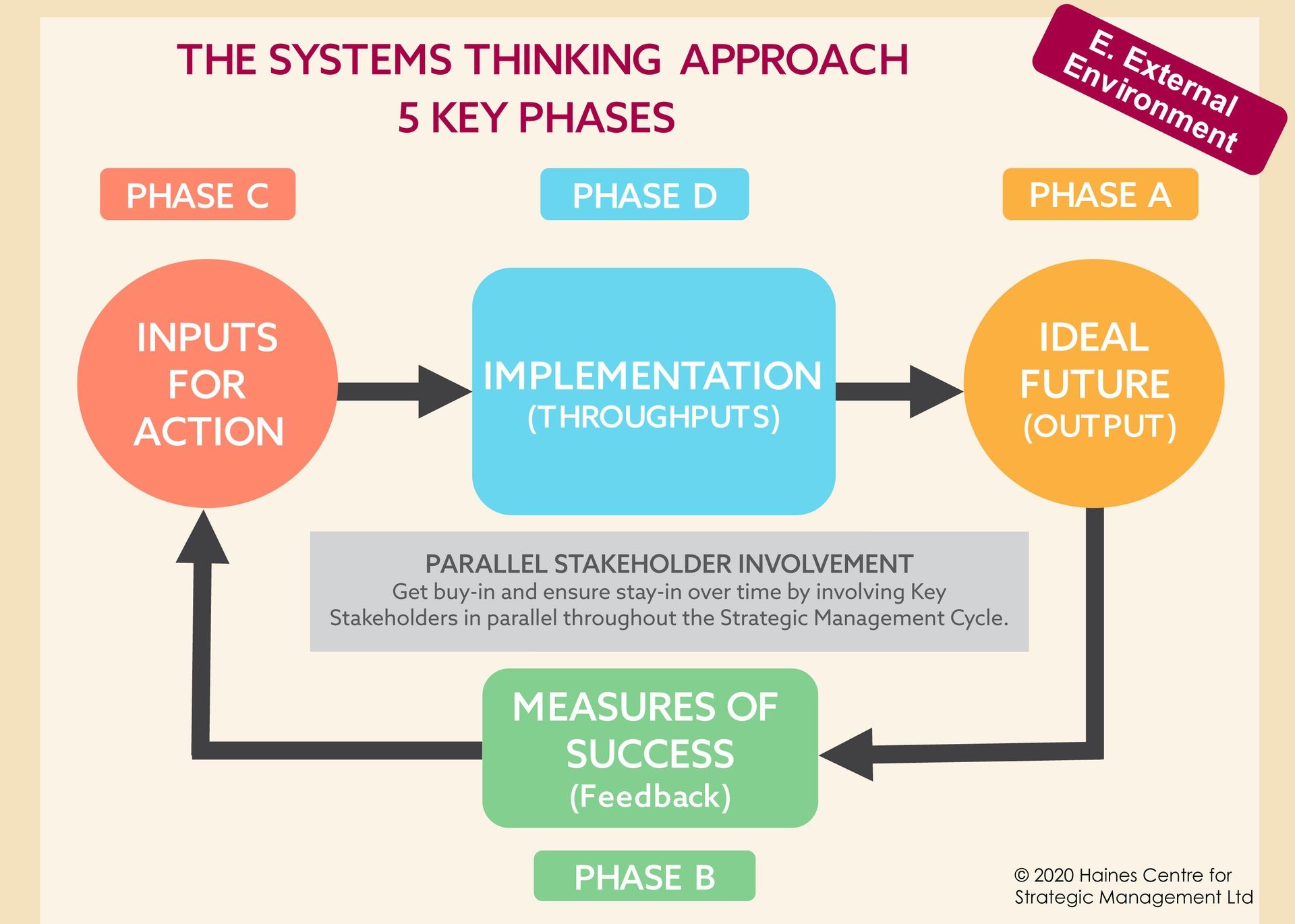

The conceptual linchpin of the Systems Thinking mindset is that all systems are circular entities. Based on the actual nature of systems, this concept is integral to the input-transformation-output-feedback model that forms the framework for Systems Thinking and reflects the natural order of life.

Once you get accustomed this mindset, complexities fade away and your perspective is like that of an astronaut—you’re taking a higher — but more accurate — view of the world, seeing it as it really is, not as people wish it to be or assume it is because of Machine Age ideas.

Paradigm Shifts

Just because analytic thinking is a common mode of thought doesn’t mean that it is correct.

Over the last century, there have been many changes in the basic assumptions or Weltanschauung. These paradigm shifts have caused some intelligent and powerful people to eat their words. Here are just a few examples:

• “Everything that can be invented has been invented.”

- Charles H. Duell, director of the U.S. Patent Office, 1899

• “Sensible and responsible women do not want to vote.”

- President Grover Cleveland, 1905

• “There is no likelihood that man can ever tap the power of the atom.”

- Robert Millikan, Nobel laureate in psychics, 1923

• “Who the hell wants to hear actors talk?”

- Harry Warner, Warner Brothers Pictures, 1927

• “I think there’s a world market for about five computers.”

- Thomas Watson, CEO of IBM, 1943

• “The Internet is just a passing fancy.”

- Bill Gates, CEO of Microsoft, 1995

SYSTEMS THINKING

In short, the world can no longer be comprehended as a simple machine.

It is a complex, highly interconnected system.

The basic trouble is that most people are still trying to solve the problems of a complex, living system with the mentality and tools that were appropriate for the world as a simple machine.

The kind of thinking and actions we generally use in our social systems has led to both spectacular successes and spectacular failures — intractable chronic problems we can’t seem to solve.

But adding an understanding and use of Systems Thinking will improve problem-solving and solution-seeking.

Systems are a set of components that work together for the overall objective of the whole (output).

Systems Thinking is finding patterns and relationships, and learning to reinforce or change these patterns to fulfill your vision and mission.

Systemic Change is a change that affects the entire body or system. It is a shift from seeing elements, functions and events to seeing the processes, structures, and interrelationships and their desired outcomes.

Systems Thinking is a discipline for seeing the whole, a framework for seeing patterns and interrelationships — which is especially important as the world grows more complex.

Unchecked, complexity can overwhelm and undermine, causing us to think, “It’s the system. I have no control.”

Systems Thinking makes these realities more manageable. It’s the antidote for feelings of helplessness.

By seeing the patterns that lie behind events and details, we can actually simplify life.

Strategic and Systems Thinking is superior to analytic thinking because of its results.

Remember: How you think, is how you plan, is how you act—and that determines your results in life and work.

SUMMARY

Analytic thinking divides larger problems into smaller ones, causing other problems that could easily be addressed with a holistic Systems Thinking Approach®. But analytic thinking is so ingrained in our thinking that we might not even be aware when we’re doing it.

Don’t worry, there are tell-tale signs of analytic thinking. Look for these clues in your organization.

Top Ten Clues to Analytic Thinking

You know you are in the presence of analytic thinking when:

Clear purposes or outcomes are missing from discussions.

People are asking or debating artificial either/or questions.

Discussions are about the one best way to do something without asking those closest to the issues for their solutions.

Discussions are focused on a direct cause and effect without considering circular causality or environmental factors.

Simplistic knee-jerk solutions and quick fixes are suggested without digging for multiple root causes.

Issues and projects are separated into silo discussions rather than looking for the relatedness, impact and their integration with other parts of the enterprise.

Discussions are activity-oriented without clarity of purpose.

An early project activity is an assessment of the situation (SWOT) instead of first starting with a Future Environmental Scan and Desired Outcomes.

Decisions are made without first exploring their unintended consequences.

Feedback and openness are being sacrificed in the name of politeness and fragile egos.

And perhaps most obvious, in analytic thinking, the complexity of the discussions, terminology and proposed solutions will make them die of their own weight.

Remember, simplicity wins the game every time.

In summary, as living systems, we are governed by the natural laws of life, so a successful participant must learn the rules. Analytic thinking is old mechanistic thinking.

The Systems Thinking Approach® is an absolute necessity to understand and succeed in today’s complex world. It is the bottom line to growing your business and life successfully.

I love to talk to you about how you can use both Systems Thinking and analytical thinking!

Be the strategic leader you were meant to be.